If You Say Something Is “Likely,” How Likely Do People Think It Is?

The wide variation of likelihood people attach to certain words immediately jumps out

Photo Credit : Lee Powers | Getty Images

People use imprecise words to describe the chance of events all the time “It’s likely to rain,” or “There’s a real possibility they’ll launch before us,” or “It’s doubtful the nurses will strike.” Not only are such probabilistic terms subjective, but they also can have widely different interpretations. One person’s “pretty likely” is another’s “far from certain.” Our research shows just how broad these gaps in understanding can be and the types of problems that can flow from these differences in interpretation.

In a famous example (at least, it’s famous if you’re into this kind of thing), in March 1951, the CIA’s Office of National Estimates published a document suggesting that a Soviet attack on Yugoslavia within the year was a “serious possibility.” Sherman Kent, a professor of history at Yale who was called to Washington, D.C. to co-run the Office of National Estimates, was puzzled about what, exactly, “serious possibility” meant. He interpreted it as meaning that the chance of attack was around 65%. But when he asked members of the Board of National Estimates what they thought, he heard figures from 20% to 80%. Such a wide range was clearly a problem, as the policy implications of those extremes were markedly different. Kent recognized that the solution was to use numbers, noting ruefully, “We did not use numbers…and it appeared that we were misusing the words.”

Not much has changed since then. Today people in the worlds of business, investing, and politics continue to use vague words to describe possible outcomes. Why? Phil Tetlock, a professor of psychology at the University of Pennsylvania, who has studied forecasting in depth, suggests that “vague verbiage gives you political safety.”

When you use a word to describe the likelihood of a probabilistic outcome, you have a lot of wiggle room to make yourself look good after the fact. If a predicted event happens, one might declare: “I told you it would probably happen.” If it doesn’t happen, the fallback might be: “I only said it would probably happen.” Such ambiguous words not only allow the speaker to avoid being pinned down but also allow the receiver to interpret the message in a way that is consistent with their preconceived notions. Obviously, the result is poor communication.

To try to address this type of muddled communications, Kent mapped the relationship between words and probabilities. In the best-known version, he showed sentences that included probabilistic words or phrases to about two dozen military officers from the North Atlantic Treaty Organization and asked them to translate the words into numbers. These individuals were used to reading intelligence reports. The officers reached a consensus for some words, but their interpretations were all over the place for others. Other researchers have since had similar results.

We created a fresh survey with a couple of goals in mind. One was to increase the size of the sample, including individuals outside of the intelligence and scientific communities. Another was to see whether we could detect any differences by age or gender or between those who learned English as a primary or secondary language.

Here are the three main lessons from our analysis.

Lesson 1: Use probabilities instead of words to avoid misinterpretation.

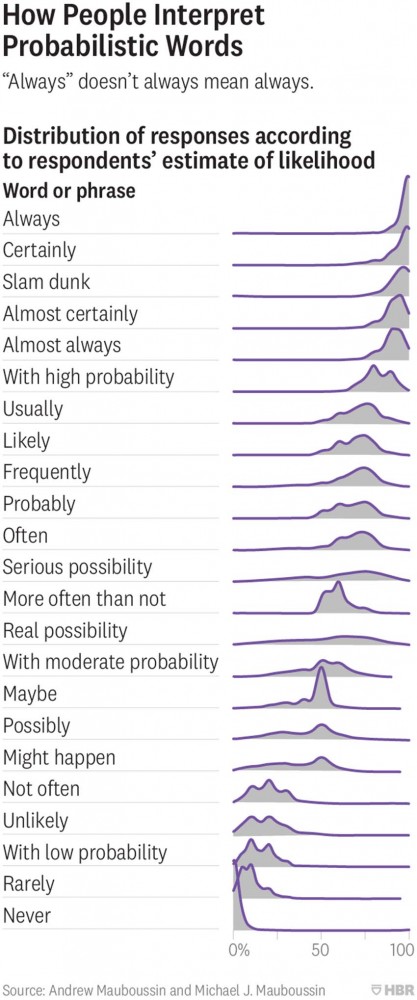

Our survey asked members of the general public to attach probabilities to 23 common words or phrases appearing in random order. The exhibit below summarizes the results from 1,700 respondents.

The wide variation of likelihood people attach to certain words immediately jumps out. While some are construed quite narrowly, others are broadly interpreted. Most but not all people think “always” means “100% of the time,” for example, but the probability range that most attribute to an event with a “real possibility” of happening spans about 20% to 80%. In general, we found that the word “possible” and its variations have wide ranges and invite confusion.

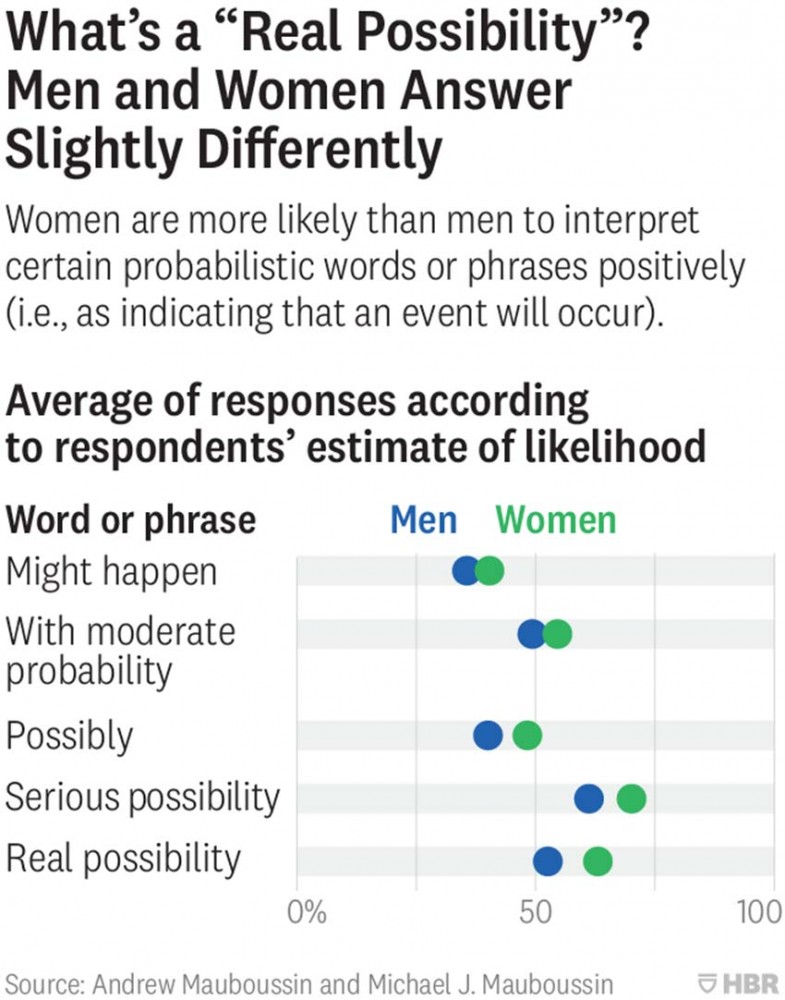

We also found that men and women see some probabilistic words differently. As the table below shows, women tend to place higher probabilities on ambiguous words and phrases such as “maybe,” “possibly,” and “might happen.” Here again, we see that “possible” and its variations particularly invite misinterpretation. This result is consistent with analysis by the data science team at Quora, a site where users ask and answer questions. That team found that women use uncertain words and phrases more often than men do, even when they are just as confident.

We did not see meaningful differences in interpretation across age groups or between native and non-native English speakers, with one exception: the phrase “slam dunk.” On average, the native English speakers interpreted the phrase as indicating a 93% probability, whereas the non-native speakers put the figure at 81%. This result offers a warning to avoid culturally biased phrases in general and sports metaphors in particular when you’re trying to be clear.

For matters of importance where mutual understanding is vital, avoid nonnumerical words or phrases and turn directly to probabilities.

Lesson 2: Use structured approaches to set probabilities.

As discussed, one reason people use ambiguous words instead of precise probabilities is to reduce the risk of being wrong. But people also hedge with words because they are not familiar with structured ways to set probabilities.

A large literature shows that we tend to be overconfident in our judgments. For example, in another survey we asked respondents to answer 50 true or false questions (for example, “The earth’s distance from the sun is constant throughout the year”) and to estimate their confidence. More than 11,000 people participated. The results show that the average confidence in answering correctly was 70%, while the average number of questions answered correctly was just 60%. Our respondents were overconfident by 10 percentage points, a finding that is common in psychology research.

Studies of probabilistic forecasts in the intelligence community stand in contrast. More-experienced analysts are generally well calibrated, which means that over a large number of predictions, their subjective guesses about probabilities and the objective outcomes (what actually occurs) align well. Indeed, when calibration is off, it is often the result of underconfidence.

How do you set probabilities intelligently?

When the odds are ambiguous, unlike in a simple gambling situation (where there’s a 50% chance of heads or tails), you are dealing with what decision theorists call subjective probabilities. These do not purport to be the correct probability, but do reflect an individual’s personal beliefs about the outcome. You should update your subjective probability estimates each time you get relevant information.

One way to pin down your subjective probability is to compare your estimate with a concrete bet. Let’s say that a competitor is expected to launch a new offering next quarter that threatens to disrupt your most profitable product. You are trying to assess the probability that the introduction doesn’t happen. The way to frame your bet might be: “If the product fails to launch, I receive $1 million, but if it does launch, I get nothing.”

Now imagine a jar full of 25 green marbles and 75 blue marbles. You close your eyes and select a marble. If it’s green, you receive $1 million, and if it’s blue, you get nothing. You know you have a one in four chance (25%) to get a green marble and win the money.

Now, which would you prefer to bet on: the launch failure or the draw from the jar?

If you’d go for the jar, that indicates that you think the chance of winning that bet (25%) is greater than the chance of winning the product-failure bet. Therefore, you must believe the likelihood of your competitor’s product launch failing is less than 25%.

In this way, using an objective benchmark helps pinpoint your subjective probability. (To test other levels of probability, just mentally adjust the ratio of green and blue marbles in the jar. With 10 green marbles and 90 blue ones, would you still draw from the jar rather than take the product-failure bet? You must think there’s less than a 10% chance the product won’t launch.)

Lesson 3: Seek feedback to improve your forecasting.

Whether you’re using vague terms or precise numbers to describe probabilities, what you’re really doing is forecasting. If you assert there’s “a real possibility” your competitor’s product will launch, you’re predicting the future. In business and many other fields, being a good forecaster is important and requires practice. But simply making a lot of forecasts isn’t enough: You need feedback. Assigning probabilities provides this by allowing you to keep score of your performance.

Opinion writers and public intellectuals often talk about the future, but typically they don’t express their convictions precisely enough to allow for accurate performance tracking. For example, an analyst might speculate, “Facebook will likely remain the dominant social network for years to come.” It’s difficult to measure the accuracy of this forecast because it is subjective and the probabilistic phrase suggests a wide range of likelihoods. A statement like “There is a 95% probability that Facebook will have more than 2.5 billion monthly users one year from now” is precise and quantifiable. What’s more, the accuracy of the analyst’s forecast can be directly measured, providing feedback on performance.

The best forecasters make lots of precise forecasts and keep track of their performance with a metric such as a Brier score. This type of performance tracking requires predicting a categorical outcome (Facebook will have more than 2.5 billion monthly users) over a specified time period (one year from now) with a specific probability (95%). It’s a tough discipline to master, but necessary for improvement. And the better your forecasts, the better your decisions. A few online resources make the task easier. The Good Judgment Open (founded by Tetlock and other decision scientists) and Metaculus provide questions to practice forecasting. Prediction markets, including PredictIt, allow you to put real money behind your forecasts.

The next time you find yourself stating that a deal or other business outcome is “unlikely” or, alternatively, is “virtually certain,” stop yourself and ask: What percentage chance, in what time period, would I put on this outcome? Frame your prediction that way, and it’ll be clear to both yourself and others where you truly stand.

This article originally appeared on : Harvard Business Review

-

Asia hit hardest by climate and weather disasters last year, says UN

2024-04-23 -

Denmark launches its biggest offshore wind farm tender

2024-04-22 -

Nobel laureate urges Iranians to protest 'war against women'

2024-04-22 -

'Human-induced' climate change behind deadly Sahel heatwave: study

2024-04-21 -

Moldovan youth is more than ready to join the EU

2024-04-18 -

UN says solutions exist to rapidly ease debt burden of poor nations

2024-04-18 -

Climate impacts set to cut 2050 global GDP by nearly a fifth

2024-04-18 -

US sterilizations spiked after national right to abortion overturned: study

2024-04-13 -

Future of Africa's flamingos threatened by rising lakes: study

2024-04-13 -

Corporate climate pledge weakened by carbon offsets move

2024-04-11